A new study at Oregon State University has concluded that significant outbreaks of viruses may be associated with coral bleaching events, especially as a result of multiple environmental stresses.

One such event was documented even as it happened in a three-day period. It showed how an explosion of three viral groups, including a herpes-like virus, occurred just as corals were bleaching in one part of the Great Barrier Reef off the east coast of Australia.

The findings, reported in Frontiers in Microbiology, take on special significance as the world is now experiencing just the third incidence ever recorded of coral bleaching on a global scale, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

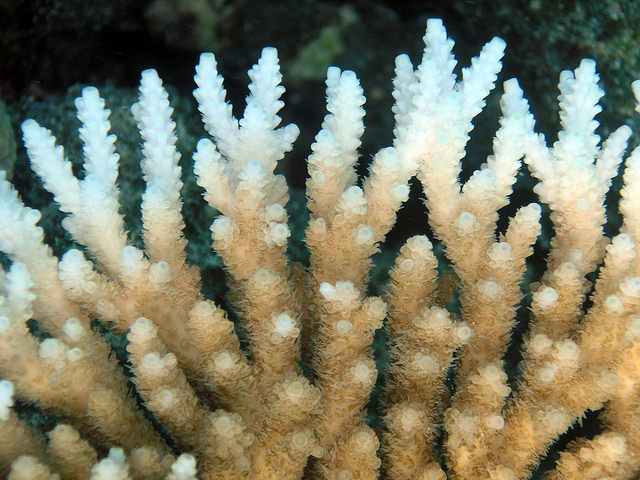

Coral bleaching can occur when corals are exposed to stressful environmental conditions, such as warmer water, overfishing or pollution. This can cause them to expel symbiotic algae that live in their tissues and lose their color. The coral loses its major source of food and is more susceptible to disease. In severe or prolonged cases the bleaching can be lethal to the corals.

“People all over the world are concerned about long-term coral survival,” said Rebecca Vega-Thurber, an assistant professor of microbiology in the OSU College of Science and corresponding author on the study. “This research suggests that viral infection could be an important part of the problem that until now has been undocumented, and has received very little attention.”

In a natural experiment, an area of corals on the Great Barrier Reef was exposed to high levels of ultraviolet light at low tides during a period of heavy rain and high temperatures, all of which are sources of stress for the corals. At that time, viral loads in those corals exploded to levels 2-4 times higher than ever recorded in corals, and there was a significant bleaching event over just three days.

The viruses included retroviruses and megaviruses, and a type of herpes virus was particularly abundant. Herpes viruses are ancient and are found in a wide range of mammals, marine invertebrates, oysters, corals and other animals.

The findings, Vega-Thurber said, suggest that a range of stresses may have made the corals susceptible to viral attack, particularly high water temperatures such as those that can be caused by an El Nino event and global warming.

“This is bad news,” Vega-Thurber said. “This bleaching event occurred in a very short period on a pristine reef. It may recover, but incidents like this are now happening more widely all around the world.”

Last year, NOAA declared that the world was now experiencing its third global coral bleaching event, the last two being in 1998 and again in 2010. The current event began in the northern Pacific Ocean in 2014, moved south during 2015, and may continue into this year, NOAA officials said.

NOAA estimated that by the end of last year, almost 95 percent of U.S. coral reefs were exposed to ocean conditions that can cause corals to bleach. If corals die, there will be less shoreline protection from storms, and fewer habitats for fish and other marine life.

Viruses are abundant, normal and diverse residents of stony coral colonies, the researchers noted in their study. Viruses may become a serious threat only when their numbers reach extremely high levels, which in this case was associated with other stressful environmental conditions, researchers said.