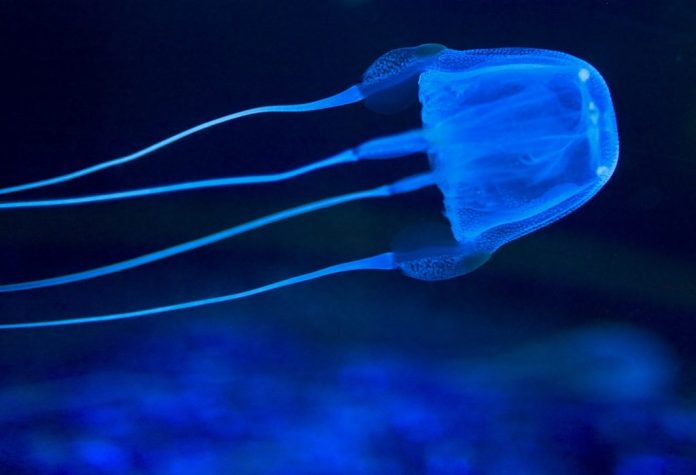

Australian and Chinese scientists have identified an antidote to the venom of the much-feared box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) that, in mice at least, suppresses the extreme pain and tissue death that usually follow a sting.

The researchers, led by Greg Neely from Australia’s University of New South Wales, suggest their technique also could be applied to toxins from other animals – but just dealing with the box jellyfish would be a great start.

The species is one of the most venomous in the world: stings are incredibly painful, and severe exposure can lead to death within minutes.

Until now, the mechanism behind this rapid and dramatic response has been unclear, and hence many current treatments have limited effect. None is able to directly target pain or local tissue death – the most common clinical outcomes of venom exposure.

A major obstacle to developing new treatments has been the limited molecular understanding of venom action.

Now, Neely and colleagues have uncovered the cellular pathways activated by toxin exposure.

Writing in the journal Nature Communications, they describe performing a genome-wide CRISPR screen to identify genes required for host cell death.

They identified several genes essential to venom cell toxicity, including those involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, and showed that interfering with them increased resistance to box jellyfish toxin.

In addition, they discovered that administering of a compound that modulates cholesterol and has been used in humans to treat Niemann-Pick Disease (a condition that affects the body’s ability to metabolise fat) reduced pain and blocked tissue death in mice when administered up to 15 minutes after exposure to the toxin.

“In summary, our unbiased screening approach has identified essential genes and cellular pathways involved in the jellyfish venom mechanisms of triggering cell death and lead to the identification of novel venom antidotes capable of suppressing pain and tissue destruction associated with envenoming,” the researchers write.

“These results highlight the power of whole genome CRISPR screening to investigate venom mechanisms of action and to rapidly identify new medicines.”