Researchers have identified the brain’s “physics engine” that helps us predict how objects in the world will behave – one of the most important aspects of cognition for survival.

Professor Jason Fischer, a cognitive scientist at Johns Hopkins University, found the source of our apparently-intuitive understanding by running a series of video-based experiments.

Computer models of towers built with Jenga-like blocks were shown to subjects, who were asked to predict which way the blocks would fall and also to guess how many blocks were yellow or blue.

Other experiments had subjects watching a video of dots bouncing around a screen, and asked them to predict their direction.

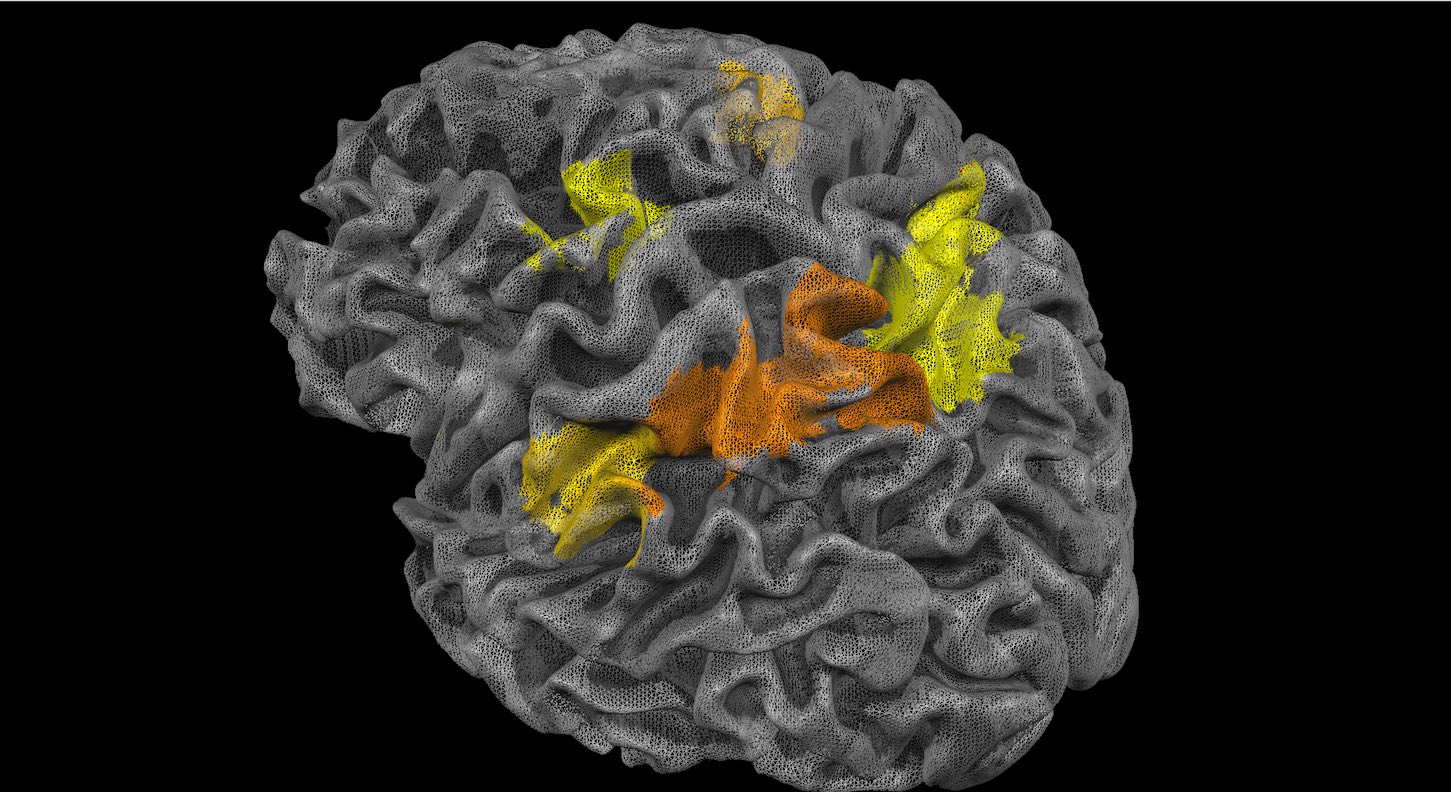

In both cases the researchers noticed that brain regions in the premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area were most responsive.

These are not areas involved with visual processing, but are associated with planning and action, the team reports in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Physical intuition and action planning are intimately linked in the brain,” said Fischer, adding this suggests the brain continually performs real-time physics calculations so people are ready to catch, dodge, or take any other appropriate action, on the fly.

“This might be because infants learn physics models of the world as they hone their motor skills, handling objects to learn how they behave.”

In the final experiments, volunteers had their brain activity monitored while watching different types of movie clip ñ some with lots of action, some with little. The scientists found a direct correlation between the physical content of a clip and the activity in those brain regions.

The findings could have practical applications in the design of better robots, which could navigate more fluidly if they are programmed to have a physical world model running constantly in the background, and in the treatment of conditions such as apraxia in which motor functions are impaired.

If nothing else, it might also give sports fans the excuse that they are in fact conducting high-level physics simulations in their heads, rather than simply watching the Olympics or Match of the Day.

Christopher B. Taub