Vast and strange donut-shaped mounds discovered behind Great Barrier Reef.

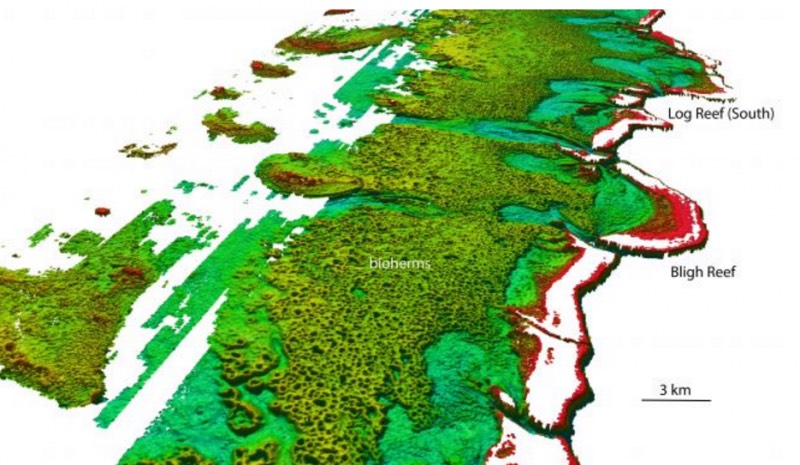

This hidden reef has huge fields of weird, doughnut-shaped mounds, each measuring 200 to 300 meters across (656 to 984 feet) and up to 10 meters deep (33 feet) at the center. Scientists knew some of these doughnuts were down there, the study’s authors explain, but only now has technology let them see the big picture.

“We’ve known about these geological structures in the northern Great Barrier Reef since the 1970s and ’80s, but never before has the true nature of their shape, size and vast scale been revealed,” says co-author Robin Beaman, a marine geologist at James Cook University, in a statement about the discovery.

“The deeper seafloor behind the familiar coral reefs amazed us,” he adds.

The doughnuts are organic structures known as “bioherms,” a type of ancient reef created over time by marine invertebrates like corals, mollusks or algae. These particular bioherms were built by Halimeda, a genus of green algae found in tropical oceans around the world. Halimeda algae are made of living calcified segments that form small limestone flakes after they die, eventually accumulating into reefs.

While bioherms were known to exist behind the Great Barrier Reef, it’s a big deal to realize they’ve developed such a huge reef — especially since it’s hidden behind the biggest, most famous reef system in the world.

“We’ve now mapped over 6,000 square kilometers. That’s three times the previously estimated size, spanning from the Torres Strait to just north of Port Douglas,” says lead author Mardi McNeil, a geoscience researcher at the Queensland University of Technology. “They clearly form a significant inter-reef habitat which covers an area greater than the adjacent coral reefs.”

The study’s authors learned this via LiDAR (short for “Light Detection and Ranging”), a remote-sensing technique that uses a pulsed laser to measure variable distance. LiDAR creates precise, 3-D maps of Earth’s surface, often by scanning the ground with lasers from an airplane or helicopter. It can even see through the sea, using green lasers to penetrate ocean water and paint a high-res portrait of what lies beneath.

The laser data were collected by the Royal Australian Navy, then analyzed by McNeil and her colleagues to reveal this deeper, subtler reef. Reported in the journal Coral Reefs, their findings could shed key light on these bioherms and the role they play in inter-reef ecosystems. And since we now know how huge this bioherm field is, they add, the danger it faces from ocean acidification looms even larger.

“As a calcifying organism, Halimeda may be susceptible to ocean acidification and warming,” notes co-author Jody Webster, a geoscience researcher at the University of Sydney. “Have the Halimeda bioherms been impacted, and if so to what extent?”

They may also help us peer back in time, Beaman adds, to better understand the region’s complex ecology and how it was affected by natural climate changes in the past. Those shifts may have happened much less quickly than modern, human-caused climate change, but they could still help us anticipate what’s coming.

“For instance, what do the 10-20 meter thick sediments of the bioherms tell us about past climate and environmental change on the Great Barrier Reef over this 10,000-year time scale?” he asks. “And, what is the finer-scale pattern of modern marine life found within and around the bioherms now that we understand their true shape?”

Jean G. Thomas