The Earth’s magnetic and geographical poles have always meandered since the beginning of time, but now they are moving at a much faster rate. This is observed through various observatories located along the Arctic Coast in northern Greenland, Canada, Russia, Sweden, and Norway. These are consistently monitoring the magnetic pull, which is also used collectively to triangulate the pole’s location. The reason it needs to be consistent, is to ensure the accuracy of the World Magnetic Model, which is responsible for all modern navigation, from ships at sea to using Google Maps on a smartphone. The World Magnetic Model is released every 5 years, with the last coming out in 2015. That version was supposed to last until 2020, but the magnetic field is changing so quickly that researchers have to fix the model now. “The error is increasing all the time,” says Arnaud Chulliat, a geomagnetist at the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Centers for Environmental Information. Researchers from NOAA and the British Geological Survey in Edinburgh have realized that it was recently so inaccurate, that it was about to exceed the acceptable limit for navigational errors. NOAA was planning on releasing the new World Magnetic Model on January 15th, but had to postpone it until January 30th on account of the ongoing government shutdown.

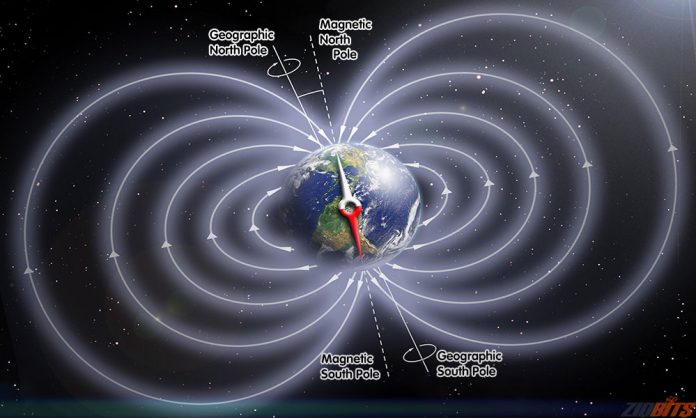

The Earth is like a giant magnet that is surrounded by a magnetic field. The field is created by a dynamo process in the fluid outer core of the Earth. The Earth’s field originates in its core. The core is comprised of iron alloys and is divided into a solid inner core and a liquid outer core. This dynamo is a process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time scales. The combination of heat, pressure, the spin of the Earth, and the relationship between the solid and liquid cores helps to create a magnetic field which is generated by a feedback loop that keeps the electric and magnetic fields building off each other.

Since 1900, the north magnetic pole has moved directly north into the Arctic Ocean just northwest of Greenland. Through the 1900s, the pole moved at about 15 kilometers per year. In the mid-1990s, it picked up speed to around 55 kilometers per year, pushing it into the Arctic Ocean by 2001. In 2018, it crossed the International Date Line into the Eastern Hemisphere, where it is currently making a beeline for Siberia. This increase in speed has been baffling scientists for the last 18 years, but the pulse that drastically altered the pole’s location in 2016 has provided a theory. These quick pole movements may be linked to a high-speed jet of liquid iron located beneath Canada. This jet may be smearing out and weakening the magnetic field beneath Canada, which is allowing for that field to lose the magnetic tug-of-war with the magnetic patch below Siberia.

This theory, if proven, can bring some insight to an unknown process. A process that takes place deep within the Earth’s core, but has innumerous impacts here on the surface. It could also point to details on how geomagnetic pole reversal has occurred in the past, and what instances may cause the magnetic poles to swap places on the globe.