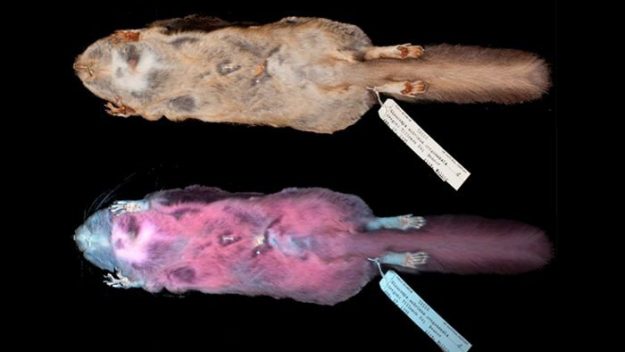

One biologist made a surprising (and colorful) discovery with an ultraviolet flashlight in a Wisconsin backyard — North America’s flying squirrels actually do glow hot pink.

Jon Martin, a biologist and professor at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, spotted the magenta-hued mammal in his UV beam. “One evening, I hear the unmistakable chirp of a flying squirrel at our bird feeder,” Martin told Newsweek. “I point the light at it and bam! Pink fluorescence.”

Martin recruited a team of researchers, including then-undergraduate student Allie Kohler, to investigate the flash of color. The team gathered specimens from a Minnesota Science Museum.

“I looked at a ton of different specimens that they had there,” Kohler said. “They were stuffed flying squirrels that they had collected over time, and every single one that I saw fluoresced hot pink in some intensity or another.”

To expand the search, gather more specimens and confirm their pink theory, Kohler and the team also went to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

In an article published last week in the Journal of Mammology, the researchers wrote that they studied 135 museum squirrels specimens in total, and found only members of the Glaucomys genus — New World flying squirrels — glimmered pink.

Three different species of flying squirrel — southern, northern and Humboldt’s flying squirrel — turned that color under ultraviolet illumination.

Researchers are not sure why the creatures’ fur turns pink, but they think it might help them recognize each other when there isn’t much light, the team told Newsweek.

The bright color could also possibly help them avoid predators, such as owls, which also fluoresce in the same hue themselves, so a flying squirrel may look, superficially at least, like a flying owl.

But the researchers say future work still need to delve into what’s behind the Day-Glo hues. If it’s confirmed that the squirrels see UV, the color might also have something to do with mating or signaling to other flying squirrels.

“It could also just be not ecologically significant to the species,” Kohler said. “It could just be a cool color that they happen to produce.”

As the research develops, she said, the importance of this find will present itself more clearly.

“It could potentially help with the conservation of the species or other species, and it could also relate to wildlife management,” Kohler said in a press release. “The more that we know about the species, the more we can understand it and help it. This is opening a new door to the realm of nocturnal-crepuscular, or active during twilight, communication in animals.”