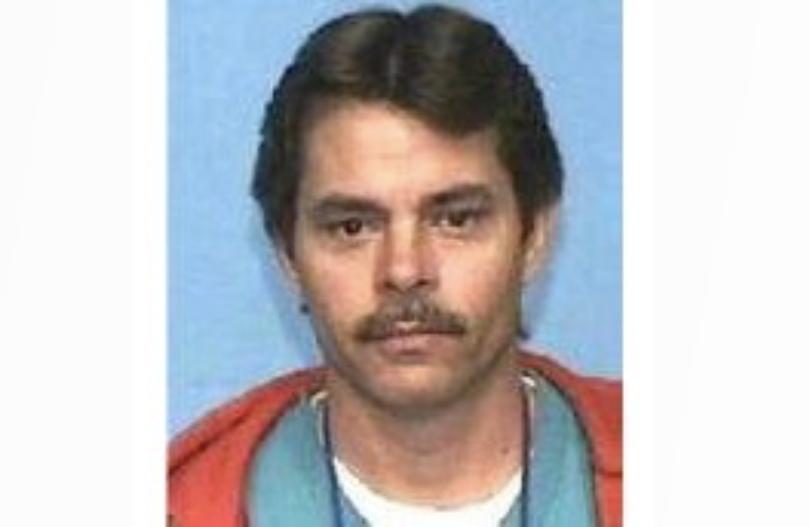

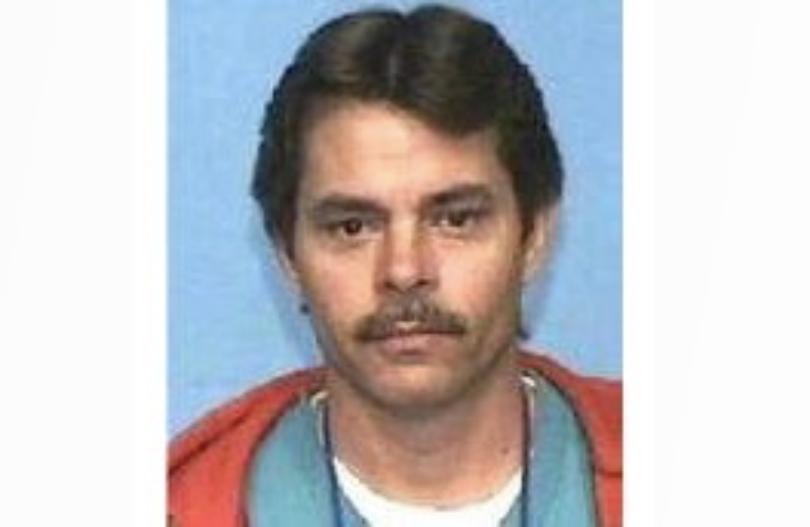

Robert Brashers: DNA links 3 murders to serial killer who died.

When 28-year-old Genevieve “Jenny” Zitricki was found beaten and strangled to death in her apartment’s bathtub, no one knew that nearly 30 years would go by before the killer would be revealed.

“Everybody was looking for patterns,” said Bush Banton, a retired detective who led the Zitricki case in 1990.

Police in Greenville have cleared the cold case after advancements in DNA testing linked a “violent serial rapist and murderer” to Zitricki’s killing, a case that spurred a brutal path of crime across the country, Police Chief Ken Miller announced Friday.

The man was recently identified as Robert Eugene Brashers. He died in a hospital from a self-inflicted gunshot wound on Jan. 19, 1999, six days after an encounter with police in Kennett, Missouri.

Zitricki’s death is believed to be one of the first attacks in a series of murders and assaults Brashers committed on women and children across four states, according to Greenville police.

“He attacked her as she slept,” Miller said of Brashers. “He bludgeoned her, strangled her and sexually assaulted her.”

Brashers first came onto law enforcement’s radar when he was charged with beating and shooting a woman in Port St. Lucie, Fla. He served three and a half years in prison and was released in 1989. Less than a year later, he killed Zitricki in Greenville.

Authorities in Missouri determined Brashers was behind the double murder of Sherri Scherer and her 12-year-old daughter, Megan, who were shot to death in their home in Portageville, Missouri on March 28, 1998. Police said Megan was also sexually assaulted.

A few hours later and across state lines in Dyersburg, Tenn., investigators say Brashers shot another woman while he tried to force his way into her home. The woman fended him off and survived the attempted murder.

From the Tennessee shooting, the survivor came up with a description of the man and a sketch was made that was displayed across the country. That sketch, and the string of cases, was featured on the television show “America’s Most Wanted” in 2009. Still, no one came forward with an identity.

More than 150 leads had yielded no results in Greenville, according to investigators. Despite the DNA match linking Zitricki’s murder to the double murder in Missouri, investigators were unable to come up with a person behind the DNA.

Investigators said Friday that new DNA technology managed to uncover Bashers’ identity.

The Greenville Police Department worked with authorities in Tennessee to use the assistance of Parabon NanoLabs, Inc., a vertically integrated DNA technology company that develops forensic products to advance DNA processing. Parabon uses genetic genealogy to trace family members to a DNA match and formally produce an identity of an individual in question.

Investigators obtained DNA samples from Brashers’ surviving family members. Last week his remains were exhumed in Arkansas by court order. Additional DNA samples taken there conclusively matched Brashers to crimes across several states in the 1990s, including the murders of Sherri and Megan Scherer and the 1997 sexual assault of a 14-year-old near Memphis.

Zitricki was found in her bathtub at least two days after her killing when a maintenance worker came in and discovered her. The bathtub was filled with water. Authorities investigating the case said they believed the killer beat her to death in her bedroom, then dragged her body to the bathroom where he submerged her in water to cover up any physical evidence.

A trail of blood went from the bedroom to the bathroom, about 20 feet away. The killer also used pantyhose that was tied around her neck to drag her through the apartment. Nothing was stolen. The contents of Zitricki’s purse were also dumped in her sink, which was also full of water.

Records show Brashers lived at an apartment now called The Park at Benito at 25 Pelham Road in Greenville.

Zitricki was an Ohio native and recent divorcee who was a systems programmer for Michelin. She lived in what was once the Hidden Lakes apartment complex on Villa Road. She lived alone, but was a social and outgoing “fireball,” said her brother, Phillip Hegedusich.

“We do well to remember her in life,” Hegedusich said. “She was a force of nature, a firecracker, a bundle of infectious energy. An intelligent, vibrant and caring human being.”

Hegedusich, who lives in New York, attended Friday’s announcement, saying it was something he would never miss after waiting so long for answers.

“Twenty-eight years. Twenty-eight years. It’s been a long time. It’s been time enough for trails to go cold,” Hegedusich said, addressing members of the media and local and state law enforcement leaders who filled the room. “We thank you for your persistence, your teamwork and your zeal to proceed.”

Hegedusich said he was always kept informed of the Police Department’s progress through the years, but began to grow weary.

“Over the course of 28 years, there were some false starts,” he said. “You start taking things with a little bit of salt.”

Miller, the police chief, said some investigators who had already been retired were brought back in to work the case. He said the Police Department worked tirelessly to find a suspect.

Banton, the retired detective, described the news of Brashers’ identity as a “relief.”

“We never gave up. Everybody kept trying and trying and trying to solve this,” he said. “It’s one of those cases you never let go.”

With new DNA technology in the hands of law enforcement, investigators in Greenville are reviewing other cold cases to determine if evidence can be put through the same tests.

The cost of the Parabon service was about $4,500, paid by law enforcement in Memphis. The Greenville Police Department paid to exhume Brashers’ remains from his grave site at a cost of about $1,300, said Lt. Jason Rampey.

Parabon combines comparative DNA analysis with traditional genealogy research known as Snapshot DNA analysis. The type of genetic genealogy focuses on autosomal DNA single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or DNA SNPs, that determine how closely related two individuals may be.

Cases that were once believed to have grown cold, may have new life, Miller said. Authorities across state lines are taking a closer look at Brashers. Some of his potential crimes may still be unsolved.

“It’s extremely possible there could be other cold cases or other sexual assaults,” Miller said.

Miller said Brashers’ identity highlights the importance for police agencies to expedite the testing of sexual assault evidence kits in the event there are DNA matches that can link suspects to victims.

An exact motive for Zitricki’s killing is still undetermined, but Sgt. Tim Conroy said he believes Brashers may have preyed on her as a target because she was outgoing. He said she would host pool parties at her apartment complex and often would allow party-goers to use her unit to use the bathroom.

While Brashers’ suicide means he won’t be held accountable for his actions through the criminal justice system, Conroy said investigators are still “relieved to know he hasn’t harmed anyone else” since his death.

“None of these efforts can bring Jenny back. We can only hope that this day brings peace to her soul and peace to her family,” Miller said.