The history of the spice trade conjures up exotic images of caravans plying the Silk Road in storied antiquity, as well as warfare between European powers vying for control of what, pound for pound, were among the most valuable commodities in the known world.

One of the most valuable of the spices was clove—the versatile immature bud of the evergreen clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum) which is native to the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas in the Indonesian Archipelago. Prized for its flavour and aroma, and also for its medicinal qualities, clove quickly became important for its use as a breath freshener, perfume, and food flavouring.

We believe we might have found the oldest clove in the world at an excavation in Sri Lanka, from an ancient port which dates back to around 200BC. This port, Mantai, was one of the most important ports of medieval Sri Lanka and drew trade from across the ancient world. Not only that, but we also found evidence for black pepper (Piper nigrum), another high-value, low-bulk product of the ancient spice trade.

Western knowledge of Sri Lanka dates back to at least 77AD, when the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote about the island as Taprobane in his famous Natural History. This is the earliest existing text which mentions Sri Lanka, however Pliny states that the ancient Greeks (and Alexander the Great) had long known about it.

Sri Lanka, wrote Pliny, “is more productive of gold and pearls of great size than even India,” as well as having “elephants … larger, and better adapted for warfare than those of India.” Fruits were abundant and the people had more wealth than the Romans—as well as living to 100 years old. No wonder then, that ancient Sri Lanka drew trade ships not only from the Roman world, but also from Arabia, India, and China.

Decades of archaeological exploration has sought to uncover evidence for the rich kingdoms of ancient Sri Lanka. Mantai (also written as Manthai and known as Manthottam/Manthota), on the northern tip of the island, was one of the port settlements of the Anuradhapura Kingdom (377BC to 1017AD) and has been recently radiocarbon dated to between about 200BCE and 1400AD.

Today, the site is barely visible from the ground—but it is still an important location with Thirukketheesvaram temple sitting in the centre of the ancient settlement. From the air, the defensive ditch and banks of ancient Mantai can be seen covered in trees, as can the area where the defences were cut away to build the modern road.

The site was excavated in the 1980s—during three seasons of excavation an amazing array of artefacts were uncovered, including semiprecious stone beads and ceramics from India, Arabia, the Mediterranean, and China. But in 1983 Sri Lanka’s civil war broke out, bringing an end to archaeological exploration in the Northern Province, as well as many other areas of the island. Unfortunately, many of the records related to this archaeological work became lost or were destroyed, including detailed stratigraphic information of how the layers of soil excavated related to one another, which would have been used to identify how and when the site developed, prospered, and came to an end.

Mantai revisited

In 2009-2010, after the end of the civil war, a multinational team of researchers went back to Mantai and began new excavations. Work was jointly carried out by the Sri Lankan Department of Archaeology, SEALINKS, and the UCL Institute of Archaeology. This project aimed to collect as much evidence from these excavations as possible, including fully quantified and systematically collected archaeobotanical (preserved plant) remains. The plants remains recovered include some of the most exciting finds from the site. Crucially, these include what were incredibly valuable spices at the time when they were deposited at the site: black pepper and cloves.

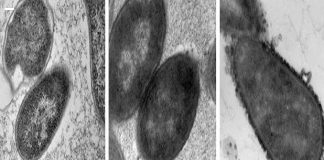

Only a handful of cloves have previously been recovered from archaeological sites, including these from France, for example—other archaeological evidence for cloves, such as pollen from cess pits in the Netherlands, only dates from 1500AD onwards—and there are no examples from south Asia.

Only a handful of cloves have previously been recovered from archaeological sites, including these from France, for example—other archaeological evidence for cloves, such as pollen from cess pits in the Netherlands, only dates from 1500AD onwards—and there are no examples from south Asia.