The tiny remains of an extinct bug-like creature discovered at B.C.’s 500-million-year-old Burgess Shale fossil deposit add a new branch to the evolutionary tree of life, says a PhD student who tracked down the organism’s development.

The discovery of fossilized soft tissue, including the unique digestive tract, antennae and appendages of extinct agnostids help solve a long-standing evolutionary riddle about the agnostids’ family tree, says Joe Moysiuk, an ecology and evolutionary biology PhD student at the University of Toronto.

The peer-reviewed study, published Wednesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B in the U.K., links the agnostids to trilobites as distant cousins. Evolutionary researchers have pondered if trilobites were related to agnostids and the new research proves the connection, Moysiuk said.

“Agnostids appear to be what we call the sister group, sort of like a distant cousin of trilobites,” he said. “They are more closely related to other trilobites than other anthropods, like say, crustaceans or like arachnids, spiders and such.”

Trilobites, which are also extinct, are similar to today’s horseshoe crabs, Moysiuk said.

Moysiuk and paleontologist Jean-Bernard Caron, an associate evolutionary biology professor at the University of Toronto and a senior curator at the Royal Ontario Museum, conducted the research.

Moysiuk said their research also helps answer questions about the origins of agnostids, which lived between 520 million and 450 million years ago.

The work emphasizes the importance of continued exploration at Burgess Shale to trace the evolutionary process of other species, Moysiuk said.

“This is an animal that’s been a big mystery in terms of where it fits into the tree of life for a very long time and so it’s always nice to fit in a little piece of the puzzle,” he said.

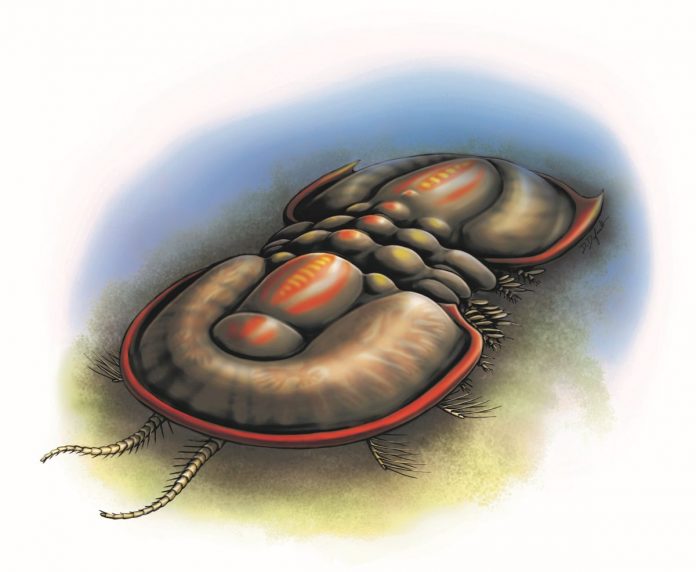

Agnostids are typically less than a centimetre long, with armour plates on their backs, a circular head shield and a similar looking tail shield, he said.

Moysiuk said finding the agnostids in the Burgess Shale area is important because not only is the hard, shell-like part of the creature preserved, but so is the soft tissues such as its nervous system and digestive tracts, sometimes even containing the last meal of the animal.

“These fossils really give us this unparalleled insight into what life was like back in the Cambrian period.”

He said the discovery of the crustacean-like soft tissue was “even weirder than what we would have imagined.”

They found a pair of sensory antennae at the front of the animals’ body and two pairs of swimming appendages, that it would have used like oars to paddle its way through the water, he said.

“They have lots of segments and these strange sort of club-like outgrowth coming off of them, which we hypothesize may have been used for respiration in these animals. So they were breathing through their legs, potentially,” he said.

Moysiuk said he’s been at the Marble Canyon site at Kootenay National Park where the fossils were found, but spends much of his time at the Royal Ontario Museum, where there’s a huge collection of fossils from Burgess Shale.