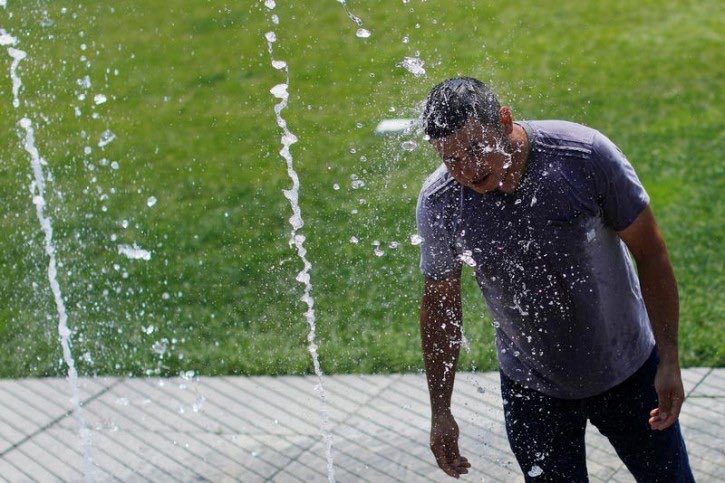

Deadly heatwave kills 33 people in Quebec.

“We’re doing the best that we can do,” Quebec’s Public Health Minister Lucie Charlebois said at a press conference Thursday. “You know, we’re living something special. In French we say, ‘C’est une situation exceptionnelle.’”

With temperatures exceeding 30 degrees Celsius, Environment Canada heat warnings have been in effect for large swathes of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia for much of the past week. The extreme heat is expected to finally abate this evening.

The 33 Quebec deaths include 18 in Montreal.

According Dr. Mylene Drouin, regional director of Montreal’s public health department, those who died were predominantly men aged 53 to 85 who lived alone and without air conditioning.

“First they have heat stroke, but most of the people who die, they are vulnerable,” Drouin told CTV Montreal. “Or (they have) problems with drugs, or they are intoxicated. So first, they’re dehydrated.”

Those living in poorer areas with less vegetation have been suffering the most during the heat wave, Drouin added during a press conference.

“In the centre of the city where we have more hot spots, where there is less greener areas, we know that compared to what is measured at the meteorological station, we can have a difference of five to 10 degrees,” she explained.

Emergency services increased

This is not the first time that Quebec has experienced such deadly heat, with more than 100 people dying during another heat wave in 2010.

“I’m not pleased about that,” Charlebois said of her province’s current crisis. “I would not like my mother to die because it’s too hot today.”

To deal with the heat wave, Urgences-sante, Montreal’s emergency medical service, has placed nine additional ambulances on the roads to respond to a 30 per cent spike in calls. At the ongoing Montreal International Jazz Festival, which runs until July 7, the number of on-scene paramedics has been doubled.

Firefighters, meanwhile, have been going door-to-door to check on at-risk people. Such people, Drouin explained, are those with “chronic diseases, mental health issues, people who live alone, (and) people without air conditioning who live in apartments of more than four or six stories.”

Public health officials are also encouraging Montrealers to check on their neighbours, especially if they are elderly.

“I’m satisfied with the work that has been done to help those who are most vulnerable,” Drouin said.