Tyrannosaurus rex may have reigned as “king of the tyrant lizards” 65 million years ago, but 185 million years before that, a reptile about the size of an iguana was the king of Antarctica.

At least that’s the message contained in the name of a fossil that’s described in a newly published research paper — and is now part of the permanent collection at Seattle’s Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

The fossil was collected during an expedition to the frozen continent led by Christian Sidor, who is the museum’s curator of vertebrate paleontology as well as a biology professor at the University of Washington. Sidor and two colleagues, the University of the Witwatersrand’s Roger Smith and Brandon Peecook of Chicago’s Field Museum, laid out the story behind the fossil in a paper published today by the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Antarctanax shackletoni takes its scientific name from the ancient Greek words for “Antarctic king” and from early-20th-century polar explorer Ernest Shackleton.

“This new animal was an archosaur, an early relative of crocodiles and dinosaurs,” Peecook, who was a UW doctoral student at the time of the expedition, said in a news release. “On its own, it just looks a little like a lizard, but evolutionarily, it’s one of the first members of that big group. It tells us how dinosaurs and their closest relatives evolved and spread.”

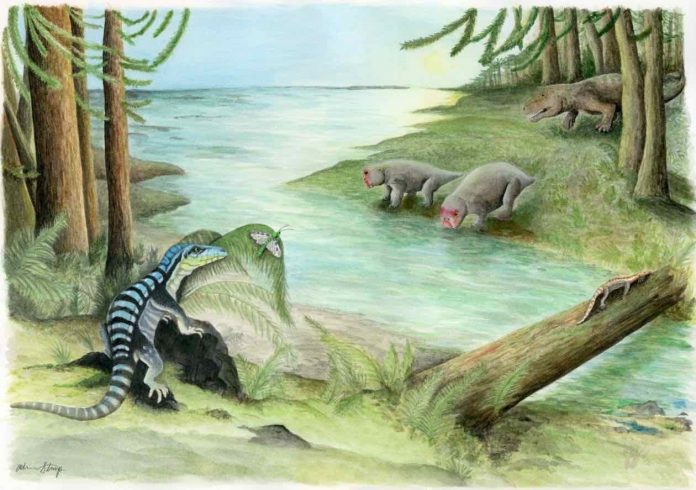

Antarctica wasn’t such a frozen continent 250 million years ago. Back then, it was part of Gondwana, a temperate supercontinent that was covered in forests and rivers — and was teeming with plants and animals.

“The more we find out about prehistoric Antarctica, the weirder it is,” Peecook said. “We thought that Antarctic animals would be similar to the ones that were living in southern Africa, since those land masses were joined back then. But we’re finding that Antarctica’s wildlife is surprisingly unique.”

Based on Antarctanax’s place in the fossil record, researchers surmise that it thrived about 2 million years after history’s biggest die-off, known as the Permian-Triassic extinction. That catastrophic event cleared the biological slate and opened the way for an evolutionary boom dominated by archosaurs like Antarctanax.

“Before the mass extinction, archosaurs were only found around the equator, but after it, they were everywhere,” Peecook said. “Antarctica had a combination of these brand-new animals and stragglers of animals that were already extinct in most places. … You’ve got tomorrow’s animals and yesterday’s animals, cohabitating in a cool place.”

The fossil described in the paper published today adds to evidence suggesting that ancient Antarctica was a hothouse for evolution.

It’s not so easy to track down that evidence. “Fossil exploration in Antarctica is really difficult, given all of the logistics involved,” Sidor said. “But since so little work has been done, the potential for making important new discoveries is high — and that’s what Antarctanax represents.”

Sidor has led four fossil-hunting expeditions to Antarctica, most recently during the 2017-2018 field season. That visit focused on Graphite Peak, where the first Antarctic vertebrate fossils were discovered in 1967 and where Antarctanax was found during Sidor’s 2010-2011 expedition.

The Antarctanax fossil skeleton is incomplete, but in their paper, Peecook, Smith and Sidor suggest that the creature was a carnivore that hunted bugs, amphibians and the ancient relatives of present-day mammals. Sidor and his colleagues collected scores of fossils left behind by those Triassic amphibians and mammal relatives during last winter’s expedition.

The Burke Museum is currently closed to the public for the transfer of collections from the museum’s old home, built in 1962, to the New Burke Museum next door. Antarctanax and other treasures from the museum’s collection will be on display when the New Burke opens this fall.