Ancient Irish genomes show mass migration to Emerald Isle from Middle East and Europe.

Genome sequencing and DNA analysis of the remains of people living 5,000 years ago in what is now Ireland uncovered the origins of its population.

The effects of migration on discoveries in archaeology divides experts. Some argue the great switch in the British Isles from hunter-gatherers to farming and from the stone to metal ages was due to local adoption of new ways.

Others claim the influences were derived from the arrival of migrants. By sequencing the first genomes from Irish people of different eras, scientists found unequivocal evidence of mass migration into Ireland.

These genetic influxes brought cultural change such as moving to settled farmsteads, bronze metalworking – and may have even been the origin of western Celtic language.

Geneticists from Trinity College, Dublin and archaeologists from Queen’s University Belfast studied the genome of a woman farmer who lived 5,200 years ago near what is now Belfast. They also carried out DNA analysis of three men on Rathlin Island from 4,000 years ago in the Bronze Age after metalworking began.

Ireland has intriguing genetics with several important diseases including excessive iron retention, or haemochromatosis.

The origin of this heritage had been unknown.

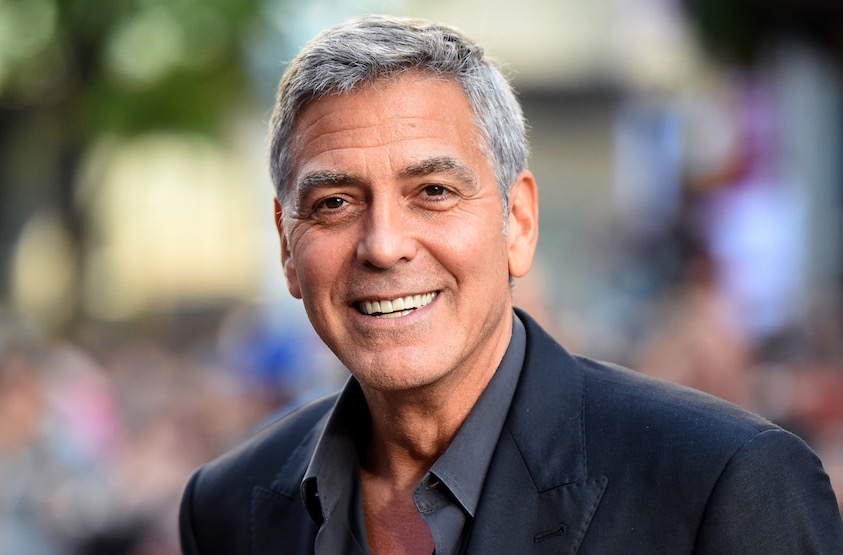

The early farmer’s ancestry originated ultimately in the Middle East, where agriculture started. She had black hair and brown eyes – like current south Europeans – and her head was reconstructed, left.

The Bronze Age male genomes are different again with one-third of their ancestry from the Pontic Steppe. They had the most common Irish Y chromosome type, the blue eye gene variant.

Dan Bradley, Trinity professor of population genetics, said: “There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe. It washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island.”