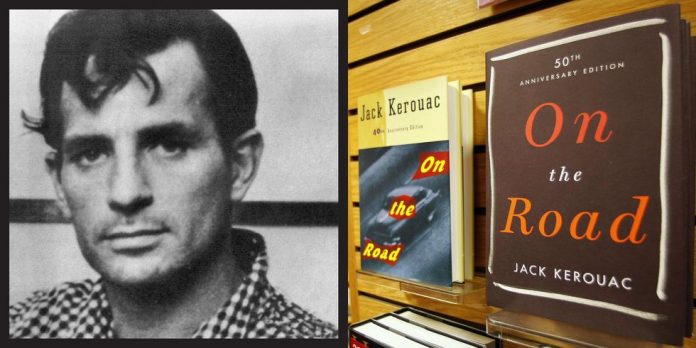

When Jack Kerouac’s On The Road appeared in 1957, it changed not only the idea of the classic American novel, but the whole notion of what a novel could be, and it did it in such an entertaining and easy-to-eat way that the whole concept of literature was suddenly taken from college professors in tweed jackets, turtle necks and jaunty goatees and passed down to anyone who could read.

English majors rejoiced.

With On The Road, the great American road trip was legitimized at the same time the great American novel was democratized. Suddenly students, readers and even highbrow professors could enjoy the act of reading so much that they wouldn’t even realize that their understanding of the human condition had just been elevated.

On The Road celebrated not only the movement of a road trip, but the optimism that came with it, the belief that no matter how hopeless or stagnate things had become wherever you were, there was bound to be something better somewhere else—all you had to do was get there.

On the most fundamental level, Kerouac’s novel celebrated his coast-to-coast driving adventures with his manic friend Neal Cassady, given the name Dean Moriarty in the book. Cassady took Kerouac, aka Sal Paradise, on numerous journeys from east to west, north to south, and even into Mexico. Kerouac never would have gone on any of the trips without his friend’s urging. Indeed, after several years of cross-country rambling, Kerouac returned to his Lowell, Massachusetts, home and spent most of the rest of his life there, drinking himself to death just 12 years after On The Road forced him into reluctant celebrity.

Twenty years ago I wrote a tribute to the novel. (This was back when you could get away with these things.) I proposed a story. I would follow one of Kerouac’s wanders in a car he would have used.

For my Dean Moriarty, I picked my friend and Autoweek photographer Bill Delaney. Delaney was, in a more relaxed, more responsible way, a lot like Dean Moriarty. Or as close to Dean Moriarty as I was going to get. He was the guy I picked when I needed someone who wouldn’t whine like an artist, who could camp out in the desert for three days and still be cheerful. He’d once helped me film a video about an Acura NSX that I thought would be a hilarious hit but which never saw the light of day (he didn’t mind). He was always ready for adventure and never wanted to quit if things got a little discombobulated. He was the perfect road-trip companion.

Cadillac, for its part, graciously provided a Sedan DeVille, something for which I am still grateful. I drove up from LA and picked up Delaney at his Ventura home, high above the rolling Pacific. We loaded the DeVille with junk food and stacks of books on Beat poetry, and we were off.

“Whooee!” yelled Dean. “Here we go!” And he hunched over the wheel and gunned her; he was back in his element, everybody could see that. We were all delighted, we all realized we were leaving confusion and nonsense behind and performing our one and noble function of the time, move. And we moved!

We hightailed it north to the Beat metropolis of San Francisco. We hung out at City Lights Bookstore, founded by Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and had a drink next door at Vesuvio, and another one at Enrico’s, both places where the Beats caroused. At 2 o’clock in the morning we found a dive motel on Lombard Street, slept a few hours, and the next day we headed east.

Reno, Battle Mountain, Elko, all the towns along the Nevada road shot by one after another, and at dusk we were in the Salt Lake flats with the lights of Salt Lake City infinitesimally glimmering almost a hundred miles across the mirage of the flats, twice showing, above and below the curve of the earth, one clear, one dim.

We spent the night just east of the Bonneville Salt Flats in Wendover, Nevada, at the Stateline Motel, because that was where Craig Breedlove stayed in 1963, and blasted east in the morning, Salt Lake City, indeed, glowing in the distance. But that was where Delaney had to fly home for another shoot. I dropped him at SLC airport and continued the trip east in the DeVille. I think it took me two more days, but it wasn’t the same without Delaney. This was before satellite radio, and if there were books on tape, I hadn’t collected any. Just wild-mouthed radio hosts and country music to fill the void.

When the story was published, City Lights hung Delaney’s Autoweek cover shot in the second-floor annex where it kept all the Beat poetry. It was the greatest honor I have ever received. I mean, Ferlinghetti himself had to have read it, right?

I lost track of Delaney after many more years and many more assignments. After a while he’d call occasionally, but he didn’t seem the same. Then last year, my friend and Autoweek colleague Jeff Vettraino, who had also become friends with Delaney over the years, sent me an obit. Delaney had died on Feb. 11, 2019, after a lifetime that included major surf films Free Ride and Surfers The Movie, among countless assignments for Autoweek and other car magazines.

I still think of Delaney from time to time. And if I ever get down about it, like Sal Paradise did, and like you can do, too, I get back into a car, and drive. Because whatever’s got you down wherever you are, there’s always bound to be something better somewhere else. You just have to get there.