Intense radiation from the giant planet Jupiter causes the night side of its moon Europa to visibly glow in the dark – a phenomenon that could help scientists learn if it can sustain simple forms of life, according to a new study.

The findings, published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy, were the result of experiments by NASA scientists to study how Jupiter’s radiation affects the chemistry of Europa, which is thought to harbor a subsurface ocean of water.

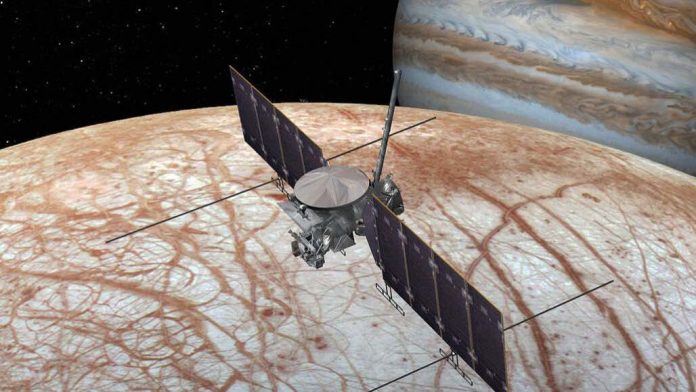

And though telescopes haven’t yet observed the glow, the possibility that Europa glows in the dark could be verified by two probes that will study the moon in the coming years.

The researchers built a below-freezing “ice chamber” at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to contain the chemicals thought to be on Europa’s icy surface and exposed it to a beam of high-energy electrons to simulate the radiation from Jupiter.

“We saw that whenever we shot it with the electron beam, it glowed,” Murthy Gudipati, an astrophysicist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead author of thestudy, said. “And when the electrons were switched off, the glow went off.”

The radiation that hits Europa is caused by Jupiter’s vast magnetosphere – the most powerful magnetic field anywhere in the solar system apart from the sun. It’s thought to be generated by metallic hydrogen in the giant planet’s highly-pressurized core.

Jupiter’s magnetosphere forms an invisible flat disk up to 12 million miles wide – much larger than the roughly million-mile wide orbit of Europa. Its radiation would kill a human being on Europa’s surface in a few seconds.

Because the simulated radiation in the experiments is also intense, the researchers studied its interactions remotely with cameras, according to Gudipati.

As well as seeing evidence of key chemical and physical changes in Europa’s crust, Jupiter’s radiation breaks water ice into oxygen and hydrogen, boosting the chances that oxygen filters down to the liquid ocean below – the researchers observed the ice visibly glowed.

The scientists then changed the chemicals thought to be mixed with ice on Europa’s surface – such as the “table salt” sodium chloride and the “Epsom salt” magnesium sulfate – and discovered differently salted ice glows with different intensities and sometimes different colors: greenish, bluish or white.

It was a moment of serendipity, Gudipati said.

“We realized that this ice glow can be controlled by what kind of material is there,” he said.

Calculations indicate Europa’s glow would look like the light from a full moon on a beach on Earth, he said.

That means it could be bright enough to be detected on the night side of the moon by nearby spacecraft, such as the Europa Clipper probe expected to arrive there before the end of this decade, and that its measurements could distinguish surface areas with different chemistries, Gudipati said.

Europa Clipper project scientist Bob Pappalardo, a planetary geologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said the probe’s main purpose will be to confirm Europa’s subsurface ocean and assess the chances that microbes could live there.

Only fossils are expected to remain of any life that evolved on Mars or Venus billions of years ago, he said. And while other gas-giant moons, such as Saturn’s Enceladus, are also thought to have subsurface water, they don’t have the intense radiation thought to create the necessary chemicals for life in Europa’s ocean.

But the radiation that makes life more likely on Europa could also harm Europa Clipper, which means the probe will only dive close enough – between 15 and 60 miles above its surface – for brief periods and spend most of its orbit much further away.

“We call it a toe-dip,” Pappalardo said. “It’s like running down and sticking your toe in the water, and then running away because it’s cold.”

Planetary scientist Andrew Coates at University College London, who has worked on several space probes, said he thinks Europa’s glow might also be visible to the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission – Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer – which is due to arrive in 2029.

“The spectrum of the glow would give more clues about the subsurface ocean,” he said in an email.