Unknown part of brain that lets you play piano (Study).

With its 86 billion neurons, the human brain is the most complex thing we know of. And it does not give up its secrets without a fight. That makes achievements like Thursday’s important.

Australian scientists have just announced the discovery of an until-now-unknown region of the brain: an unexplored land, living just under our skulls.

The newly-charted region, which so far has not been seen in other animals, may be responsible for extremely fine motor control – our unique ability to play piano or perform surgery.

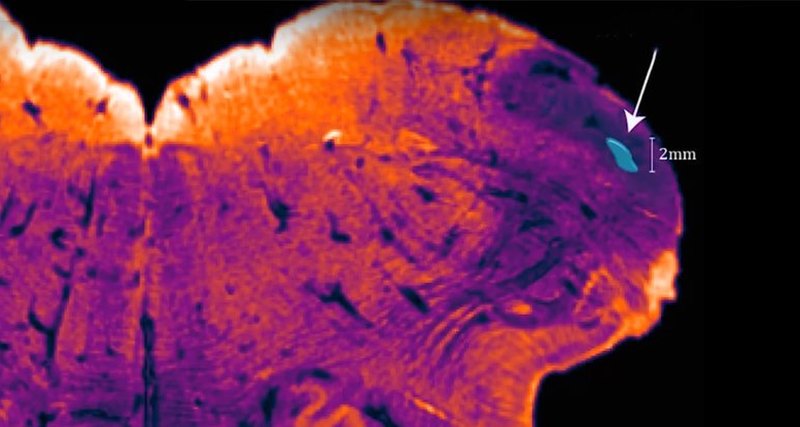

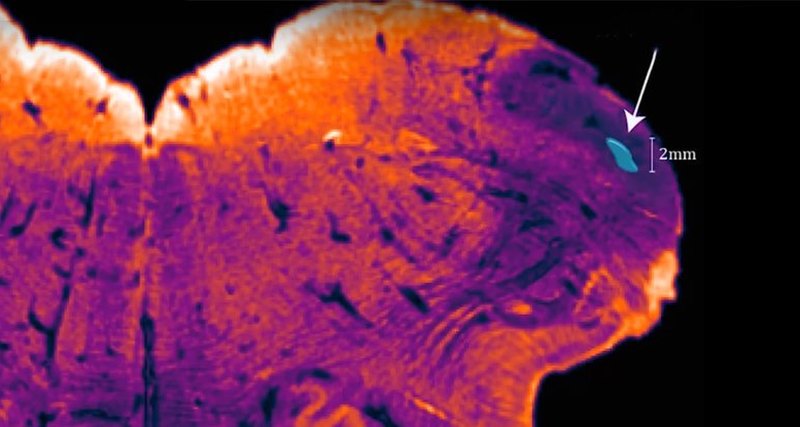

It’s about the size of a pea and sits at the back of the skull, right at the base of the brain. Its discoverer, NeuRA’s brain cartographer Professor George Paxinos, has christened it the Endorestiform Nucleus.

“It found me. It was staring me in the face for 30 years,” he says.

Professor Paxinos has spent more than 40 years using a 4B pencil to hand-draw extraordinarily detailed maps of the human brain.

He is one of Australia’s most important scientists and his brain atlases are among the most-cited publications in neuroscience and are used in surgery.

His newly-found region is embedded in a major neural highway that links the spinal cord and the brain. This part of the brain is known to be involved in how we control the movement of our limbs and body.

Generally, human brains look a lot like monkey brains – just bigger. But when Professor Paxinos went looking for his new region in other animals, he couldn’t find it. It seems to be a unique part of the human brain involved in movement control.

What movements can we make that monkeys cannot? Perhaps the Endorestiform Nucleus is linked to our unique ability to move our fingers with great precision, Professor Paxinos speculates.

“Monkeys, you don’t see them playing pianos, do you?” he says.

But Professor Paxinos is just the map-maker – now that he’s found the new region, it is up to other scientists to work out what it does.

He’s found many regions before but this discovery is particularly special, because it brings him full circle. Twenty-eight years ago when he published his first atlas of the brain stem, “I saw something unusual in this area. Some cells that were very striking”.

“But I wasn’t bold enough to say this was a separate structure.”

For the new edition, out soon, he decided to go back to this curious spot and study it intensely for a couple of days. Almost immediately he noticed it really was different – an island of separate cells, with their own unique connections and chemistry.

“If anything I would say how silly I was not to have looked at this in more detail 30 years ago,” he laughs.

To start a new atlas, the team cuts a sample brain horizontally into about 200 ultra-thin slices.

These are then photographed in extremely high resolution, and blown up to 1 metre x 1 metre prints before being placed on tables around a space the size of a lecture hall.

Professor Paxinos can then walk through a giant representation of the brain and trace its neuron highways and backroads.

“He’ll hold his pencil and his magnifying glass over each region,” says Dr Steve Kassem, a postdoc in his lab.

“He picks one tiny box, and then follows it through about 100 pictures from start to end, to try to follow the different structures that should exist in this area.”

When he found this latest region, as he has with every new place he has charted, he stopped and took a step back.

His long-time collaborator and co-author Charles Watson wandered to the back of their lab in Sydney and pulled out a saxophone.

Professor Paxinos sat, and Professor Watson put his fingers to the brass keys and played. And, together, they enjoyed the feeling of discovery.